“Men are able to have the family and step up because women step back in terms of their jobs, but both are deprived. Men forgo time with their family and women often forgo their career,” these are the words of Nobel Laurette Claudia Goldin who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for her work in the area of female participation in the labour market and the gender pay gap.

In this Blog, I will try to interpret the major aspects of Professor Goldin’s research over the years.

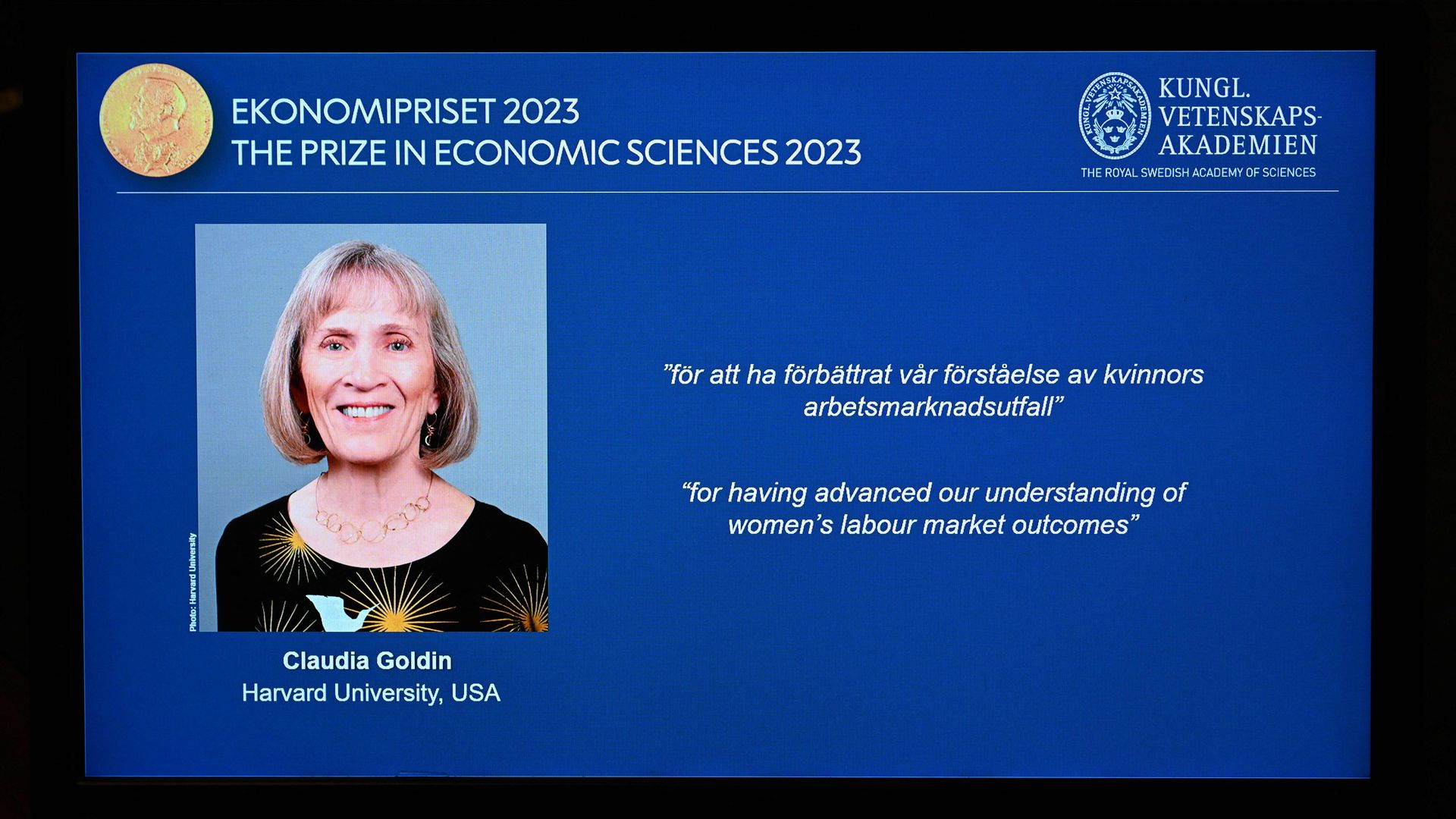

Nobel Prize (Economics) 2023

The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences 2023, was awarded to Harvard Professor and historian economist Claudia Goldin. The 77-year-old received the prestigious award for “advancing our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes”. She is only the third woman to ever receive the prize, and the first to not share the award with male colleagues. The first one was Elinor Ostrom who was awarded jointly with Oliver E Williamson for research on economic governance. Then in 2019, Esther Duflo shared the award with her husband Abhijit Banerjee, and Michael Kremer, for work that focused on poor communities in India and Kenya.

According to the Nobel Committee, before Goldin’s book was published in 1990, data mainly from the 20th century had been published. It was believed that as the economy grew the female participation too would increase. However, Goldin found that this is not the case. She trawled through the archives of about 200 years of data to demonstrate how and why gender differences in earnings and employment rates have changed over time.

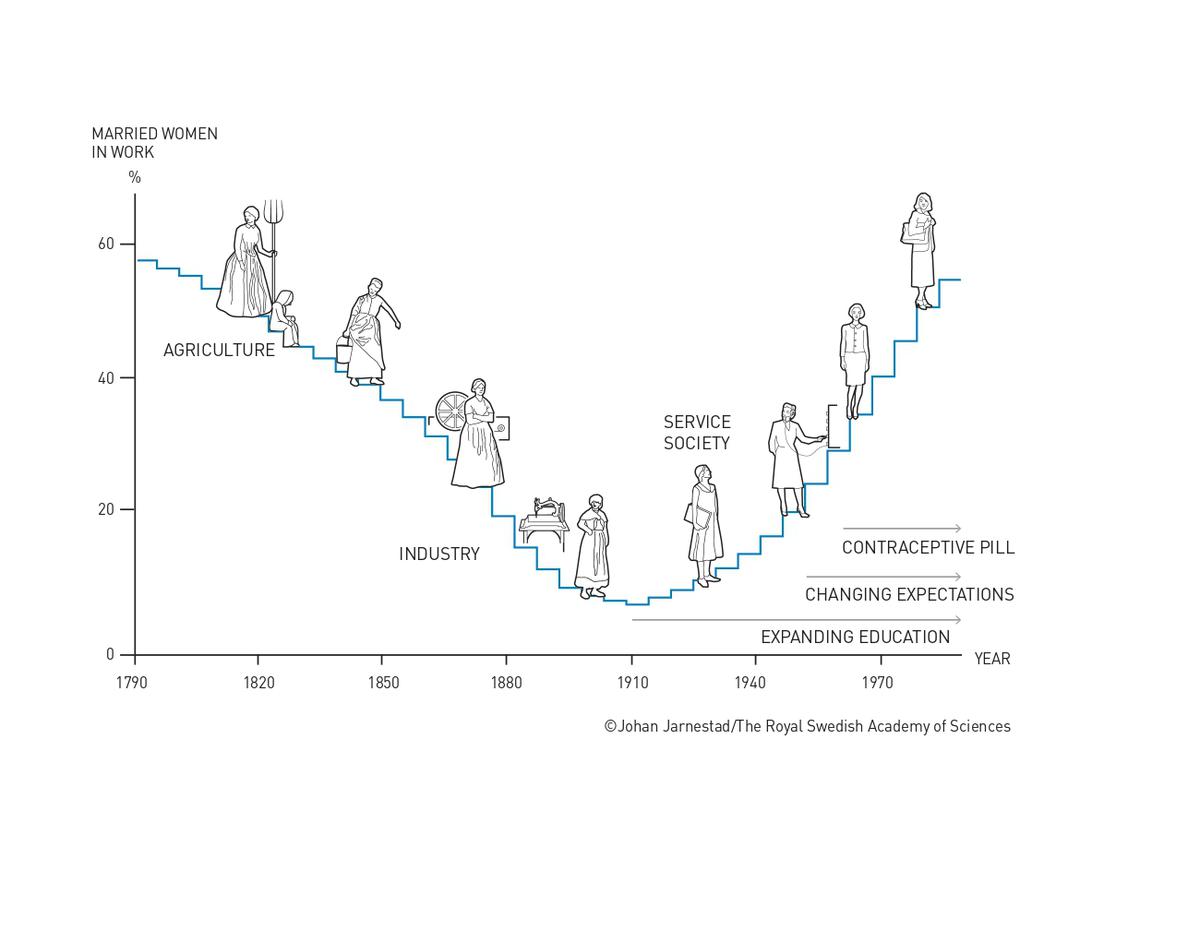

The U-shaped curve showing female labour participation over the years (Photo: The Hindu)

The ‘U-shaped Curve’ of Female Labour Participation

Professor Goldin demonstrated that several factors have historically influenced and still influence the supply and demand for female labour. According to her findings, while 80% of men participate in the labour market globally, only 50% of women do the same, and at the same time, women earn less and are less likely to reach the top of the career ladder.

One of her first findings was that women’s participation was “incorrectly assessed” throughout, historically in Censuses and public data. A standard practice used to categorise women’s occupation only as “wife” in records. However, this practice failed to account for activities other than domestic labour such as working alongside husbands in farms, family businesses, and cottage industries. Goldin said that the proportion of women in the labour force was considerably higher at the end of the 1890s than what was shown in the official statistics.

Goldin showed that if we trace the female participation in the labour market on a graph, it doesn’t form an upward trend, but instead forms a U-shaped curve. Female participation fell in the 1800s, but their employment picked up again in the 1900s as the service economy grew.

She found that before the era of industrialisation, female participation was higher, as the major activities were related to agriculture only, and women did worked at farms, with or without their husbands. However, as industrialisation progressed, female participation fell down as women needed to go out in search of skilled jobs. Finally, with the growth of the services sector (banking, hospitality), female participation again picked up with the rise in the education level of women.

Claudia Goldin with her husband Lawrence and dog Pika, after the announcement (Photo: X@NobelPrize)

‘Marriage and Contraception’

Goldin’s work highlighted two factors crucial in women’s access to education and employment; marriage and contraceptive pills. At the start of the 20th century, Goldin found that while 20% of women were part of the labour force, the number was only 5% for married women. Also, there were several legislations known as “marriage bars” which stopped married women from entering some specific fields such as teachers or office workers. This trend peaked during the Great Depression when even under heavy demand females weren’t given many opportunities.

By the 1960s, contraceptives started coming into trend. This gave female better options in controlling their pregnancies and planning their careers. With advancement, women also started marrying later and had better control over their careers. Now women also indulged in studying previously explored fields like law, medicine and economics. With this, the women started catching up in the chart and their participation increased. Goldin has described the 1970s in particular as a “revolutionary period” in which women in the United States began to marry later, take strides in higher education, and make major progress in the labour market.

The Role of Expectations

A very important finding of Goldin’s study was that women’s expectations were based on the experience of their mothers, and thus their educational and professional decisions were not taken with the expectation of having a long, uninterrupted, and fruitful career. This factor is still relevant and shows how important it is today to present the female child with the same upbringing, as is given to the male child.

Goldin says in her work that, “The exit for an extended period after marriage also explains why the average employment level for women increased by so little, despite the massive influx of women into the labour market in the latter half of the century”.

The role of expectations also worked in another aspect. Initially, the employers presumed that a woman would not return to work after marriage. Due to this, females were employed at lesser wages. But, things turned in the second half of the 20th century, and married women started returning to the labour force once their children got older. But, this also depended on the level of education attained by the woman. Initially, the employers “underestimated” the level of education of the female employees. But, this trend too, was overcome in the 1970s when young women invested more in their education.

Announcement of Claudia Goldin as the winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics (Photo: Axios)

The Gender Pay Gap

Despite all the developments, one glaring gap that remained over the years was that of the gender pay gap. An interesting observation from Goldin’s study was that the pay gap was much less before the industrial era, as in agricultural work, the payment depended on daily output. But, with the growth of industrialisation, the advent of monthly contracts widened this gap. The employers — being sceptic of women’s workability after having a child — give much higher contracts.

This also affected the women’s increments and other incentives. The findings also pointed out that initial pay differences were small, but they increased against women after the birth of the first child. More worryingly, it didn’t increase at the same rate as men even when the two had the same skills and education. Goldin said in an interview that she hoped people would take away from her work how important long-term changes are to understanding the labour market.

Goldin’s ‘Golden’ words

Professor Goldin also speaks about gender equality. She points out that there is a stigma in society that believes that it is the women who have to sacrifice their careers and sit back at home after marriage and children. However, she also points out that men too lose on the precious years of seeing their children growing up due to their work. She rightly points out that, societal and family structures that women and men grow up in shape their behaviour and economic outcomes. “We see a residue of history around us,” she says.

According to Goldin, “We are never going to have gender equality until we also have couple equity”. These words, in my opinion, are the perfect gist of Goldin’s whole research over the years. Also, this is something that we all should carefully look at, especially in India, where patriarchal society and societal stigma often burn out all the female potential inside a kitchen. Goldin says that while there has been monumental progressive change over the years, at the same time there are important differences, which as per the Nobel Laurette ties back to women doing more work in the home.